ইউ এস বাংলা নিউজ ডেক্স

আরও খবর

Kidnapping in Bangladesh: A Rising Epidemic Under the Interim Government

Dehumanization Of Dissenters: Yunus playbook to murder family members of student wing of Awami League

Bangladesh crisis News Yunus regime Dhaka’s Turbulent Streets: The Root of the Chaos Sits in Jamuna

Bangladesh’s Export Downturn: Four Months of Decline

Election Without Choice? Bangladesh Faces a Growing Political Crackdown

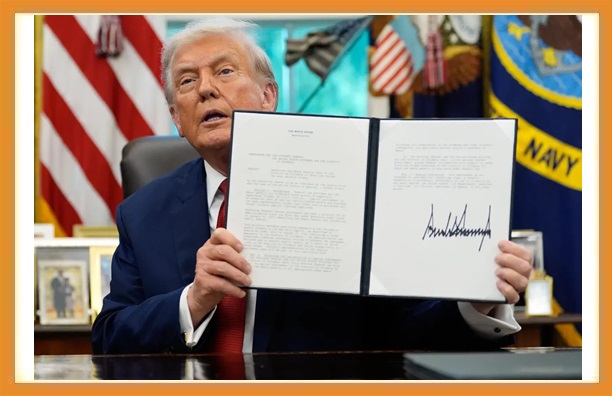

Under Donald Trump direction America on Wrong Direction

‘Ekattorer Prohori Foundation, USA’ condemns heinous attack on minority Hindu community in Rangpur

Mobocracy in robes: How Yunus regime’s farcical tribunal ordered Sheikh Hasina’s judicial assassination

The recent death penalty verdict against Sheikh Hasina, Bangladesh’s longest-serving Prime Minister, delivered by the so-called International Crimes Tribunal (ICT), fails to show any real connection between the charges framed, the evidence presented, and the conclusions reached by the court. Even more troubling is that the entire process appears designed to settle old political scores. This trial reflects a long-held desire for revenge by the ideological descendants of the 1971 war criminals whom Sheikh Hasina brought to justice. It is painful to see a judicial institution rebuilt through illegal means and reshaped in a way that seems intended to produce

a predetermined political outcome. The unelected interim administration led by Dr Muhammad Yunus came to power following a meticulously engineered campaign of mayhem, riots, disinformation, and mob violence. During July–August 2024, police stations were torched, weapons looted, critical infrastructure vandalised, and government authority systematically undermined until a democratic and elected government was toppled and replaced by a regime that has never once asked the Bangladesh’s people for a mandate. It is this regime, born of mob rule, that has now reassembled the ICT and used it to pass a sentence of death on the very prime minister who, for fifteen years,

anchored Bangladesh’s democratic and developmental trajectory. The tribunal is not a court of justice. It is a political weapon, built on constitutional defiance, judicial capture, and procedural fraud, and its verdict against Sheikh Hasina is a judicial assassination in political form. A Tribunal Rebuilt on Constitutional Rubble The first problem is not simply how the tribunal behaves; it is that it should not exist in this form at all. After 5 August 2024, the interim regime set about remodelling the International Crimes Tribunal Act, 1973 (ICTA) by decree. Within just eleven months, it issued four executive ordinances, altering more than thirty-four provisions of the

ICTA. Under Article 93(1) of Bangladesh’s Constitution, ordinances may be promulgated only when Parliament is in recess; Article 93(2) requires that every such ordinance be placed before Parliament within thirty days. Since there is no functioning Parliament now, none of these changes were ever subjected to parliamentary scrutiny or approval. They are ultra vires; beyond the constitutional powers of any interim government, null and void ab initio. In other words, the current structure of the ICT rests not on law, but on rule by decree. What was created in 1973 by a sovereign Parliament and later amended after 2009 to prosecute

the genocide and crimes against humanity of 1971 has been re-engineered by an unelected regime to prosecute the democratic opponents. The separation of powers has been replaced by a concentration of power in the hands of an administration that owes its existence to unrest, not to elections. To call this a “court” is to misuse the word. Mobocracy in Robes: How the Judiciary Was Captured The Chief Justice and other judges of the Appellate Division were forced out under orchestrated mob pressure menacing the Supreme Court complex while regime-aligned actors made clear that judges who did not fall in line would face public

humiliation and worse. This spectacle violated the Constitutional guarantee of judicial independence, and shielding of judges from arbitrary removal. It was not reform; it was mobocracy weaponised to break the bench. The tribunal itself was assembled in haste. Its entire structure was reshaped through executive orders, not through proper democratic or judicial processes. This alone creates a serious concern that the verdict against Sheikh Hasina came from a process built to reach a political goal, not to uphold justice. The regime reconstituted the ICT with judges who were either inexperienced, politically aligned, or both. Article 98 of the Constitution prohibits the appointment

of probationary (additional) judges to special tribunals. Section 6 of the International Crimes Tribunal Act (ICTA) requires that tribunal judges be senior Supreme Court judges or jurists of recognised competence. It also requires that only permanent judges of the High Court Division can serve as the Chairman of the ICT. Instead, the regime appointed Justice Md. Golam Mortuza Mazumdar, who had only just been made an additional judge of the High Court, as the Chairman of the ICT—a position requiring not only seniority but also experience in complex criminal and international law. Barrister Shafiul Alam Mahmud was appointed as a High Court judge a mere six days before being placed on the tribunal. He had never served as a judge before and has a well-documented history of being a member of the Bangladesh Nationalist Party’s lawyer organisations. Other judges Mohitul Haque, Enam Chowdhury, Nazrul Islam Chowdhury, Manzurul Basid, and Nur Md. Shahriar Kabir were selected through the same constitutionally defective, politically engineered processes. These are not technical quibbles. When a regime purges senior judges under mob pressure and replaces them with newly inducted, politically sympathetic additional judges in a special tribunal, it is not strengthening justice; it is capturing it. Credible reports that the ICT Chairman was absent during critical stages of the most politically consequential trial in Bangladesh’s history only add to the sense of farce. If the Chairman did not hear all the evidence, who actually adjudicated it? Who drafted the judgment? Were verdicts scripted elsewhere and merely read out under judicial letterhead? These questions would be alarming in any jurisdiction. In a capital case, they are devastating. Defence Rights Turned Inside Out The trial in absentia of Sheikh Hasina adds another layer of concern. Such trials are permissible only when the accused receives proper notice, voluntarily chooses not to appear, enjoys effective representation, and is guaranteed a full retrial upon return. None of these conditions were met. Sheikh Hasina had to relocate from Bangladesh not by choice but under an atmosphere of direct threat to life. The tribunal treated the guarantees of the right to adequate time and facilities to prepare a defence and the right to legal assistance of one’s own choosing as obstacles, not obligations. Senior members of the Dhaka Bar—including respected advocates such as Z.I. Panna, who explicitly sought to represent Sheikh Hasina—were obstructed from appearing. In their place, the tribunal imposed defence counsel who had no experience in international criminal law. The regime-appointed defence counsel received the prosecution’s voluminous dossier only five weeks before trial. He asked for no adjournment. He conducted minimal cross-examination, failed to challenge hearsay evidence, did not probe inconsistencies in witness testimonies, and raised no serious objections when the tribunal restricted disclosure or limited cross-examination. He called no expert witnesses, presented no independent forensic analysis, and made no effort to test the prosecution’s narrative through competing evidence. His one notable intervention—claiming that intercepted audio recordings were “AI-generated”—was made without any accompanying motion for independent forensic testing. He did not insist on authenticating the recordings and did not demand a full chronological reconstruction of events. This is not simply poor lawyering; it is the effective denial of the right to defence. A tribunal that denies the accused the lawyer of their choice and then assigns them a lawyer unable or unwilling to mount a serious challenge has already made its decision about guilt. The assault on due process did not stop there. The tribunal curtailed cross-examination, withheld exculpatory evidence, and conducted proceedings with minimal transparency, in violation of the most basic principles of natural justice. A Prosecution Built on Old Hatreds On the other side of the courtroom, the prosecution was not a neutral organ of justice but a partisan blade. The entire team is dominated by lawyers ideologically and politically aligned with Jamaat-e-Islami and other anti–Awami League factions/groups that have opposed the Bangladesh Liberation War of 1971 and resisted accountability for 1971. Some have previously defended convicted war criminals. The Chief Prosecutor, Advocate Tazul Islam, previously served as defence counsel for individuals accused of crimes against humanity before the original ICT, men who acted as auxiliary forces to the Pakistan Army during the 1971 genocide. His elevation to lead prosecutions in a tribunal now targeting the political heirs of the Liberation War is a glaring conflict of interest. This prosecutorial architecture directly offends the requirement of impartiality embedded in Article 35(3) of the Constitution, Article 14(1) of the ICCPR, the UN Basic Principles on the Independence of the Judiciary and the UN Guidelines on the Role of Prosecutors. When the judges come from a bench reshaped by mob pressure, the defence is hobbled by design, and the prosecution is staffed by individuals with deep historical grievances against the accused’s political movement, the outcome is not justice. It is a performance. A Hundred Days to Death: Justice as Theatre Complex crimes-against-humanity cases normally span years. They demand the painstaking review of vast evidentiary records, rigorous cross-examination, expert testimony, and careful judicial deliberation. Yet the reconstituted ICT rushed through the trial of Sheikh Hasina in barely one hundred days—an impossible timeline for any genuine pursuit of justice. The trial in absentia adds an even more serious layer of illegitimacy. International standards allow such trials only under strict conditions: the accused must receive proper notice; must freely choose not to appear; must have legal representation of her own choice; and must be guaranteed a full retrial upon return. None of these requirements were met. Sheikh Hasina had to relocate from Bangladesh not by choice but under an atmosphere of direct threat to life. She had no opportunity to appoint counsel she trusted, and neither she nor any supporter had confidence in the court-appointed lawyer forced upon her. The tribunal accepted the prosecution’s assertions with almost no scrutiny, reducing the proceedings to a one-sided performance. The evidentiary foundation of the verdict is equally alarming. The prosecution listed five allegations and eighty-one witnesses—many with long-standing links to anti–Awami League politics—yet produced only fifty-four. Nearly half were “experts” offering partisan commentary rather than facts. The case leaned heavily on selective bystander accounts, context-less audio fragments, a press briefing, and the testimony of a police chief who turned state witness only after receiving a promise of pardon. Such material does not approach the standard required for crimes against humanity. More troubling still, the tribunal elevated the public remarks of UN High Commissioner Volker Türk—comments never intended as legal conclusions—to the status of quasi-judicial determinations. It also accepted so-called “prosecution-verified” phone recordings, none of which show Sheikh Hasina ordering violence. The tribunal relied on them without authentication, chronology, or forensic scrutiny. Given the tribunal’s partisan composition, the crippled defence, the politically aligned prosecution, and the impossibly compressed timeline, there is only one reasonable interpretation: evidence was sidelined, deliberation was perfunctory, and the verdict was engineered long before the trial began. Reports that the tribunal’s Chairman was absent during critical phases reinforce this conclusion. The ICT did not function as a court of law; it operated as a theatrical arm of an authoritarian project, performing the rituals of justice while delivering a predetermined political sentence. What Really Happened in July–August 2024 With no attempt to ensure fair process or genuine fact-finding, the Yunus regime, its propaganda machinery, and their international allies have launched a coordinated campaign to shape global opinion, attempting to try Sheikh Hasina in the court of foreign media by claiming she personally ordered the killing of students and protesters. The facts say otherwise. From 1–15 July 2024, students exercised their constitutional right to protest freely. The elected government neither banned demonstrations nor attempted to disperse assemblies. Instead, on 11 July, the government accepted the core demands related to quota reform. Law enforcement agencies were instructed to facilitate peaceful gatherings and avoid any confrontation. During this period, whatever the political tensions, the Awami League government never treated student demonstrators as adversaries but as citizens to be heard. The situation changed dramatically after 14 July, when actors aligned with Jamaat-e-Islami and its student wing Islami Chhatra Shibir, operating within the so-called Students Against Discrimination (SAD) platform, intentionally misinterpreted a speech by Sheikh Hasina to ignite unrest. Multiple attempts were made from within the movement to provoke violence—and eventually they succeeded. Student dormitories at the University of Dhaka and other campuses came under attack. Students having affiliation with the Bangladesh Students' League (BSL) were targeted, attacked, and in Chattogram even thrown from rooftops. Both the government and the BSL attempted to de-escalate the situation, but were overwhelmed by militant extremists and violent infiltrators. By 18 July, the character of the events had changed entirely. Violent actors—unconnected to genuine student leadership—began coordinated attacks on key-point installations (KPIs), government buildings, major infrastructure and police stations, using crude bombs, petrol bombs and small firearms. Police armouries were looted, and the stolen weapons were later deployed against civilians and law enforcement. Critical communications and transport infrastructure were sabotaged. Most dangerously, NATO-grade 7.62-calibre ammunition was used in targeted killings of protesters, bystanders and even Awami League activists (like Jewel Molla of Gazipur) to inflame public fear and accelerate social collapse. Confronted with an escalating armed insurgency masquerading as a protest movement, the government did what any responsible state is obliged to do: it imposed a nationwide curfew and authorised law enforcement to act under established legal frameworks to restore order and protect lives. Crucially, there is no credible evidence that Sheikh Hasina ever ordered the use of lethal force. Bangladesh’s laws and police operational protocols already define when force may be used; the response was governed by those statutes—not by any personalised instruction. Recognising the gravity of the crisis, the elected government established a Judicial Inquiry Committee, led by a sitting High Court justice, to investigate all deaths and violence occurring between 15 July and 5 August, including casualties among protesters, civilians, Awami League activists, and police officers. The Yunus regime abruptly halted this inquiry immediately upon seizing power. That suspension was not administrative; it was political—a calculated act to bury evidence that contradicts the regime’s preferred narrative. The regime even authorized a decree of indemnity to all the violence and atrocities that took place in favour of the ouster. In the absence of a domestic inquiry, international narratives quickly hardened, often without the rigour required for judicial standards. A much-cited OHCHR fact-finding report claimed roughly 1,400 deaths between 15 July and 15 August 2024. But the figure is fraught with methodological flaws as the Ministry of Health under the Yunus regime documented 834 deaths in the same period. Many higher figures rely on anonymous, unverified, or coerced testimony. Several individuals listed as “dead” were later found alive in domestic reporting, reducing this death toll to around 782. Even the OHCHR itself admitted the report does not meet standards for judicial admissibility. It offers no disaggregated data, no time-stamped sequencing of incidents, and no methodology capable of allocating responsibility for deaths occurring before or after the collapse of the elected government. Most importantly, after midday on 5 August 2024, the elected government no longer held authority. Any casualties occurring after the government’s overthrow cannot, under any reasonable or legal standard, be attributed to Sheikh Hasina’s administration. Yet this basic chronological fact is routinely omitted in international commentary. Meanwhile, little attention has been paid to Awami League activists killed in targeted attacks during the unrest and police officers murdered in streets and in stations through violent attacks. The claims of responsibility by certain protest leaders and extremist groups for arson, sabotage and target killings are also being ignored. The substantial body of evidence that implicates other actors and exonerates Awami League supporters are being brushed aside by the blanket decree of indemnity given by the regime to shield the real perpetrators. When a court constructs a capital verdict on such contested, selective, and incomplete evidence, it is not engaging in adjudication. It is endorsing a politically curated narrative. The Broader Agenda of the Yunus Regime To understand why the ICT has been turned into a political theatre, we must look beyond the courtroom. Since seizing power, the Yunus regime has presided over a deepening crisis of governance. Public services have deteriorated. Police have been ordered to stand back as attacks on Awami League workers and cadres continue with near impunity. The Hindu community and other religious minorities have reported rising violence and intimidation. Women’s rights, painstakingly advanced under Awami League governments, have been quietly rolled back through policy neglect and concessions to conservative elements. Inside the state apparatus, figures associated with Islamist extremist networks, including individuals linked to Hizb-ut-Tahrir, have acquired new influence. Journalists and human rights defenders have been harassed, detained, and silenced. Economic growth has slowed, a trend documented by international financial institutions. Elections have been postponed, the Awami League has been banned from political participation, and segments of the electorate are effectively disenfranchised. In this wider context, the reconstituted ICT serves a clear political function. It provides a moral alibi for authoritarian consolidation: by demonising Sheikh Hasina and the Awami League as perpetrators of “crimes against humanity”, the regime seeks to justify its own illegitimate rule, distract from its failures, and remove its principal democratic rival from the field permanently. A Verdict Against Democracy Itself The death sentence against Sheikh Hasina is not an isolated judgment, it is the endpoint of an orchestrated political project. It rests on unconstitutional, ex post facto amendments, delivered by a tribunal illegally constituted with ineligible, politically aligned judges. The verdict relies on untested evidence, partisan witnesses, and a trial in absentia that violated every principle of notice, counsel, confrontation, and cross-examination. That it is shielded from meaningful appellate review makes it even more alarming in a capital case. Most troubling is its selectivity. The ICT has targeted only Awami League leaders, while those responsible for arson, looting of arms, minority attacks, and sabotage during the 2024 unrest enjoy de facto impunity. This is not justice; it is persecution. The political motive is unmistakable. Sheikh Hasina fulfilled her 2008 pledge to try the war criminals of 1971, bringing senior Jamaat-e-Islami leaders to account. Today, the prosecution is stacked with lawyers who once defended those very figures, and several tribunal judges have documented BNP–Jamaat affiliations. The courtroom has become a venue for settling old ideological scores. The verdict has triggered sweeping condemnation: 102 leading journalists and 1,001 prominent academics across universities have denounced it as retaliatory, farcical, and the product of a kangaroo court. For Bangladeshis who uphold the ideals of 1971 -- sovereignty, secularism, social justice -- this is not just an attack on a leader, but an assault on constitutional governance itself. International civil-society organisations with long-established credibility, including the European Bangladesh Forum, Earth Civilization Network, Freedom and Justice Alliance, the South Asia Democratic Forum in Belgium, and the Working Group Bangladesh in Germany have all raised serious concerns about the legitimacy of the proceedings. Major global institutions, notably Amnesty International and the International Crisis Group, have likewise warned of the absence of due process, the erosion of judicial neutrality, and the overtly political character of the charges. What the World Should See International audiences are being sold a comforting fiction: that an “interim government” is fearlessly pursuing accountability, that a “special tribunal” is dispensing justice, and that a spontaneous “mass movement” toppled an authoritarian regime. They should look much more closely. A democratically elected government was not removed by popular mandate but by orchestrated mob violence. An unelected regime then rewrote laws without Parliament, forced judges out under mob intimidation, installed partisan newcomers on the bench, crippled defence rights, assembled a prosecution driven by old vendettas, and rushed a capital trial to completion in just one hundred days, ending in a death sentence against the leader who delivered Bangladesh its greatest gains in development and social progress in a generation. Since then, the same regime has banned the Awami League from elections, is not yet definitive about holding elections, allowed extremists to infiltrate state institutions, and now governs without any democratic mandate—all while running a polished PR campaign to disguise a constitutional breakdown. In this context, the reconstituted ICT is not a solution but a symptom of the crisis: unconstitutional in its creation, compromised in its composition, fraudulent in its procedures, and selective in its prosecutions. Justice for the victims of 2024 is essential, but it will not come from a kangaroo tribunal created by an illegitimate regime. It will come only when Bangladeshis are again free to choose their representatives democratically and under the Constitution. Until then, the world must see the death sentence against Sheikh Hasina for what it is: not a ruling grounded in law, but the clearest expression yet of a regime intent on eliminating its principal democratic opponent. (The author is President of the Bangladesh Students' League. Views are personal.)

a predetermined political outcome. The unelected interim administration led by Dr Muhammad Yunus came to power following a meticulously engineered campaign of mayhem, riots, disinformation, and mob violence. During July–August 2024, police stations were torched, weapons looted, critical infrastructure vandalised, and government authority systematically undermined until a democratic and elected government was toppled and replaced by a regime that has never once asked the Bangladesh’s people for a mandate. It is this regime, born of mob rule, that has now reassembled the ICT and used it to pass a sentence of death on the very prime minister who, for fifteen years,

anchored Bangladesh’s democratic and developmental trajectory. The tribunal is not a court of justice. It is a political weapon, built on constitutional defiance, judicial capture, and procedural fraud, and its verdict against Sheikh Hasina is a judicial assassination in political form. A Tribunal Rebuilt on Constitutional Rubble The first problem is not simply how the tribunal behaves; it is that it should not exist in this form at all. After 5 August 2024, the interim regime set about remodelling the International Crimes Tribunal Act, 1973 (ICTA) by decree. Within just eleven months, it issued four executive ordinances, altering more than thirty-four provisions of the

ICTA. Under Article 93(1) of Bangladesh’s Constitution, ordinances may be promulgated only when Parliament is in recess; Article 93(2) requires that every such ordinance be placed before Parliament within thirty days. Since there is no functioning Parliament now, none of these changes were ever subjected to parliamentary scrutiny or approval. They are ultra vires; beyond the constitutional powers of any interim government, null and void ab initio. In other words, the current structure of the ICT rests not on law, but on rule by decree. What was created in 1973 by a sovereign Parliament and later amended after 2009 to prosecute

the genocide and crimes against humanity of 1971 has been re-engineered by an unelected regime to prosecute the democratic opponents. The separation of powers has been replaced by a concentration of power in the hands of an administration that owes its existence to unrest, not to elections. To call this a “court” is to misuse the word. Mobocracy in Robes: How the Judiciary Was Captured The Chief Justice and other judges of the Appellate Division were forced out under orchestrated mob pressure menacing the Supreme Court complex while regime-aligned actors made clear that judges who did not fall in line would face public

humiliation and worse. This spectacle violated the Constitutional guarantee of judicial independence, and shielding of judges from arbitrary removal. It was not reform; it was mobocracy weaponised to break the bench. The tribunal itself was assembled in haste. Its entire structure was reshaped through executive orders, not through proper democratic or judicial processes. This alone creates a serious concern that the verdict against Sheikh Hasina came from a process built to reach a political goal, not to uphold justice. The regime reconstituted the ICT with judges who were either inexperienced, politically aligned, or both. Article 98 of the Constitution prohibits the appointment

of probationary (additional) judges to special tribunals. Section 6 of the International Crimes Tribunal Act (ICTA) requires that tribunal judges be senior Supreme Court judges or jurists of recognised competence. It also requires that only permanent judges of the High Court Division can serve as the Chairman of the ICT. Instead, the regime appointed Justice Md. Golam Mortuza Mazumdar, who had only just been made an additional judge of the High Court, as the Chairman of the ICT—a position requiring not only seniority but also experience in complex criminal and international law. Barrister Shafiul Alam Mahmud was appointed as a High Court judge a mere six days before being placed on the tribunal. He had never served as a judge before and has a well-documented history of being a member of the Bangladesh Nationalist Party’s lawyer organisations. Other judges Mohitul Haque, Enam Chowdhury, Nazrul Islam Chowdhury, Manzurul Basid, and Nur Md. Shahriar Kabir were selected through the same constitutionally defective, politically engineered processes. These are not technical quibbles. When a regime purges senior judges under mob pressure and replaces them with newly inducted, politically sympathetic additional judges in a special tribunal, it is not strengthening justice; it is capturing it. Credible reports that the ICT Chairman was absent during critical stages of the most politically consequential trial in Bangladesh’s history only add to the sense of farce. If the Chairman did not hear all the evidence, who actually adjudicated it? Who drafted the judgment? Were verdicts scripted elsewhere and merely read out under judicial letterhead? These questions would be alarming in any jurisdiction. In a capital case, they are devastating. Defence Rights Turned Inside Out The trial in absentia of Sheikh Hasina adds another layer of concern. Such trials are permissible only when the accused receives proper notice, voluntarily chooses not to appear, enjoys effective representation, and is guaranteed a full retrial upon return. None of these conditions were met. Sheikh Hasina had to relocate from Bangladesh not by choice but under an atmosphere of direct threat to life. The tribunal treated the guarantees of the right to adequate time and facilities to prepare a defence and the right to legal assistance of one’s own choosing as obstacles, not obligations. Senior members of the Dhaka Bar—including respected advocates such as Z.I. Panna, who explicitly sought to represent Sheikh Hasina—were obstructed from appearing. In their place, the tribunal imposed defence counsel who had no experience in international criminal law. The regime-appointed defence counsel received the prosecution’s voluminous dossier only five weeks before trial. He asked for no adjournment. He conducted minimal cross-examination, failed to challenge hearsay evidence, did not probe inconsistencies in witness testimonies, and raised no serious objections when the tribunal restricted disclosure or limited cross-examination. He called no expert witnesses, presented no independent forensic analysis, and made no effort to test the prosecution’s narrative through competing evidence. His one notable intervention—claiming that intercepted audio recordings were “AI-generated”—was made without any accompanying motion for independent forensic testing. He did not insist on authenticating the recordings and did not demand a full chronological reconstruction of events. This is not simply poor lawyering; it is the effective denial of the right to defence. A tribunal that denies the accused the lawyer of their choice and then assigns them a lawyer unable or unwilling to mount a serious challenge has already made its decision about guilt. The assault on due process did not stop there. The tribunal curtailed cross-examination, withheld exculpatory evidence, and conducted proceedings with minimal transparency, in violation of the most basic principles of natural justice. A Prosecution Built on Old Hatreds On the other side of the courtroom, the prosecution was not a neutral organ of justice but a partisan blade. The entire team is dominated by lawyers ideologically and politically aligned with Jamaat-e-Islami and other anti–Awami League factions/groups that have opposed the Bangladesh Liberation War of 1971 and resisted accountability for 1971. Some have previously defended convicted war criminals. The Chief Prosecutor, Advocate Tazul Islam, previously served as defence counsel for individuals accused of crimes against humanity before the original ICT, men who acted as auxiliary forces to the Pakistan Army during the 1971 genocide. His elevation to lead prosecutions in a tribunal now targeting the political heirs of the Liberation War is a glaring conflict of interest. This prosecutorial architecture directly offends the requirement of impartiality embedded in Article 35(3) of the Constitution, Article 14(1) of the ICCPR, the UN Basic Principles on the Independence of the Judiciary and the UN Guidelines on the Role of Prosecutors. When the judges come from a bench reshaped by mob pressure, the defence is hobbled by design, and the prosecution is staffed by individuals with deep historical grievances against the accused’s political movement, the outcome is not justice. It is a performance. A Hundred Days to Death: Justice as Theatre Complex crimes-against-humanity cases normally span years. They demand the painstaking review of vast evidentiary records, rigorous cross-examination, expert testimony, and careful judicial deliberation. Yet the reconstituted ICT rushed through the trial of Sheikh Hasina in barely one hundred days—an impossible timeline for any genuine pursuit of justice. The trial in absentia adds an even more serious layer of illegitimacy. International standards allow such trials only under strict conditions: the accused must receive proper notice; must freely choose not to appear; must have legal representation of her own choice; and must be guaranteed a full retrial upon return. None of these requirements were met. Sheikh Hasina had to relocate from Bangladesh not by choice but under an atmosphere of direct threat to life. She had no opportunity to appoint counsel she trusted, and neither she nor any supporter had confidence in the court-appointed lawyer forced upon her. The tribunal accepted the prosecution’s assertions with almost no scrutiny, reducing the proceedings to a one-sided performance. The evidentiary foundation of the verdict is equally alarming. The prosecution listed five allegations and eighty-one witnesses—many with long-standing links to anti–Awami League politics—yet produced only fifty-four. Nearly half were “experts” offering partisan commentary rather than facts. The case leaned heavily on selective bystander accounts, context-less audio fragments, a press briefing, and the testimony of a police chief who turned state witness only after receiving a promise of pardon. Such material does not approach the standard required for crimes against humanity. More troubling still, the tribunal elevated the public remarks of UN High Commissioner Volker Türk—comments never intended as legal conclusions—to the status of quasi-judicial determinations. It also accepted so-called “prosecution-verified” phone recordings, none of which show Sheikh Hasina ordering violence. The tribunal relied on them without authentication, chronology, or forensic scrutiny. Given the tribunal’s partisan composition, the crippled defence, the politically aligned prosecution, and the impossibly compressed timeline, there is only one reasonable interpretation: evidence was sidelined, deliberation was perfunctory, and the verdict was engineered long before the trial began. Reports that the tribunal’s Chairman was absent during critical phases reinforce this conclusion. The ICT did not function as a court of law; it operated as a theatrical arm of an authoritarian project, performing the rituals of justice while delivering a predetermined political sentence. What Really Happened in July–August 2024 With no attempt to ensure fair process or genuine fact-finding, the Yunus regime, its propaganda machinery, and their international allies have launched a coordinated campaign to shape global opinion, attempting to try Sheikh Hasina in the court of foreign media by claiming she personally ordered the killing of students and protesters. The facts say otherwise. From 1–15 July 2024, students exercised their constitutional right to protest freely. The elected government neither banned demonstrations nor attempted to disperse assemblies. Instead, on 11 July, the government accepted the core demands related to quota reform. Law enforcement agencies were instructed to facilitate peaceful gatherings and avoid any confrontation. During this period, whatever the political tensions, the Awami League government never treated student demonstrators as adversaries but as citizens to be heard. The situation changed dramatically after 14 July, when actors aligned with Jamaat-e-Islami and its student wing Islami Chhatra Shibir, operating within the so-called Students Against Discrimination (SAD) platform, intentionally misinterpreted a speech by Sheikh Hasina to ignite unrest. Multiple attempts were made from within the movement to provoke violence—and eventually they succeeded. Student dormitories at the University of Dhaka and other campuses came under attack. Students having affiliation with the Bangladesh Students' League (BSL) were targeted, attacked, and in Chattogram even thrown from rooftops. Both the government and the BSL attempted to de-escalate the situation, but were overwhelmed by militant extremists and violent infiltrators. By 18 July, the character of the events had changed entirely. Violent actors—unconnected to genuine student leadership—began coordinated attacks on key-point installations (KPIs), government buildings, major infrastructure and police stations, using crude bombs, petrol bombs and small firearms. Police armouries were looted, and the stolen weapons were later deployed against civilians and law enforcement. Critical communications and transport infrastructure were sabotaged. Most dangerously, NATO-grade 7.62-calibre ammunition was used in targeted killings of protesters, bystanders and even Awami League activists (like Jewel Molla of Gazipur) to inflame public fear and accelerate social collapse. Confronted with an escalating armed insurgency masquerading as a protest movement, the government did what any responsible state is obliged to do: it imposed a nationwide curfew and authorised law enforcement to act under established legal frameworks to restore order and protect lives. Crucially, there is no credible evidence that Sheikh Hasina ever ordered the use of lethal force. Bangladesh’s laws and police operational protocols already define when force may be used; the response was governed by those statutes—not by any personalised instruction. Recognising the gravity of the crisis, the elected government established a Judicial Inquiry Committee, led by a sitting High Court justice, to investigate all deaths and violence occurring between 15 July and 5 August, including casualties among protesters, civilians, Awami League activists, and police officers. The Yunus regime abruptly halted this inquiry immediately upon seizing power. That suspension was not administrative; it was political—a calculated act to bury evidence that contradicts the regime’s preferred narrative. The regime even authorized a decree of indemnity to all the violence and atrocities that took place in favour of the ouster. In the absence of a domestic inquiry, international narratives quickly hardened, often without the rigour required for judicial standards. A much-cited OHCHR fact-finding report claimed roughly 1,400 deaths between 15 July and 15 August 2024. But the figure is fraught with methodological flaws as the Ministry of Health under the Yunus regime documented 834 deaths in the same period. Many higher figures rely on anonymous, unverified, or coerced testimony. Several individuals listed as “dead” were later found alive in domestic reporting, reducing this death toll to around 782. Even the OHCHR itself admitted the report does not meet standards for judicial admissibility. It offers no disaggregated data, no time-stamped sequencing of incidents, and no methodology capable of allocating responsibility for deaths occurring before or after the collapse of the elected government. Most importantly, after midday on 5 August 2024, the elected government no longer held authority. Any casualties occurring after the government’s overthrow cannot, under any reasonable or legal standard, be attributed to Sheikh Hasina’s administration. Yet this basic chronological fact is routinely omitted in international commentary. Meanwhile, little attention has been paid to Awami League activists killed in targeted attacks during the unrest and police officers murdered in streets and in stations through violent attacks. The claims of responsibility by certain protest leaders and extremist groups for arson, sabotage and target killings are also being ignored. The substantial body of evidence that implicates other actors and exonerates Awami League supporters are being brushed aside by the blanket decree of indemnity given by the regime to shield the real perpetrators. When a court constructs a capital verdict on such contested, selective, and incomplete evidence, it is not engaging in adjudication. It is endorsing a politically curated narrative. The Broader Agenda of the Yunus Regime To understand why the ICT has been turned into a political theatre, we must look beyond the courtroom. Since seizing power, the Yunus regime has presided over a deepening crisis of governance. Public services have deteriorated. Police have been ordered to stand back as attacks on Awami League workers and cadres continue with near impunity. The Hindu community and other religious minorities have reported rising violence and intimidation. Women’s rights, painstakingly advanced under Awami League governments, have been quietly rolled back through policy neglect and concessions to conservative elements. Inside the state apparatus, figures associated with Islamist extremist networks, including individuals linked to Hizb-ut-Tahrir, have acquired new influence. Journalists and human rights defenders have been harassed, detained, and silenced. Economic growth has slowed, a trend documented by international financial institutions. Elections have been postponed, the Awami League has been banned from political participation, and segments of the electorate are effectively disenfranchised. In this wider context, the reconstituted ICT serves a clear political function. It provides a moral alibi for authoritarian consolidation: by demonising Sheikh Hasina and the Awami League as perpetrators of “crimes against humanity”, the regime seeks to justify its own illegitimate rule, distract from its failures, and remove its principal democratic rival from the field permanently. A Verdict Against Democracy Itself The death sentence against Sheikh Hasina is not an isolated judgment, it is the endpoint of an orchestrated political project. It rests on unconstitutional, ex post facto amendments, delivered by a tribunal illegally constituted with ineligible, politically aligned judges. The verdict relies on untested evidence, partisan witnesses, and a trial in absentia that violated every principle of notice, counsel, confrontation, and cross-examination. That it is shielded from meaningful appellate review makes it even more alarming in a capital case. Most troubling is its selectivity. The ICT has targeted only Awami League leaders, while those responsible for arson, looting of arms, minority attacks, and sabotage during the 2024 unrest enjoy de facto impunity. This is not justice; it is persecution. The political motive is unmistakable. Sheikh Hasina fulfilled her 2008 pledge to try the war criminals of 1971, bringing senior Jamaat-e-Islami leaders to account. Today, the prosecution is stacked with lawyers who once defended those very figures, and several tribunal judges have documented BNP–Jamaat affiliations. The courtroom has become a venue for settling old ideological scores. The verdict has triggered sweeping condemnation: 102 leading journalists and 1,001 prominent academics across universities have denounced it as retaliatory, farcical, and the product of a kangaroo court. For Bangladeshis who uphold the ideals of 1971 -- sovereignty, secularism, social justice -- this is not just an attack on a leader, but an assault on constitutional governance itself. International civil-society organisations with long-established credibility, including the European Bangladesh Forum, Earth Civilization Network, Freedom and Justice Alliance, the South Asia Democratic Forum in Belgium, and the Working Group Bangladesh in Germany have all raised serious concerns about the legitimacy of the proceedings. Major global institutions, notably Amnesty International and the International Crisis Group, have likewise warned of the absence of due process, the erosion of judicial neutrality, and the overtly political character of the charges. What the World Should See International audiences are being sold a comforting fiction: that an “interim government” is fearlessly pursuing accountability, that a “special tribunal” is dispensing justice, and that a spontaneous “mass movement” toppled an authoritarian regime. They should look much more closely. A democratically elected government was not removed by popular mandate but by orchestrated mob violence. An unelected regime then rewrote laws without Parliament, forced judges out under mob intimidation, installed partisan newcomers on the bench, crippled defence rights, assembled a prosecution driven by old vendettas, and rushed a capital trial to completion in just one hundred days, ending in a death sentence against the leader who delivered Bangladesh its greatest gains in development and social progress in a generation. Since then, the same regime has banned the Awami League from elections, is not yet definitive about holding elections, allowed extremists to infiltrate state institutions, and now governs without any democratic mandate—all while running a polished PR campaign to disguise a constitutional breakdown. In this context, the reconstituted ICT is not a solution but a symptom of the crisis: unconstitutional in its creation, compromised in its composition, fraudulent in its procedures, and selective in its prosecutions. Justice for the victims of 2024 is essential, but it will not come from a kangaroo tribunal created by an illegitimate regime. It will come only when Bangladeshis are again free to choose their representatives democratically and under the Constitution. Until then, the world must see the death sentence against Sheikh Hasina for what it is: not a ruling grounded in law, but the clearest expression yet of a regime intent on eliminating its principal democratic opponent. (The author is President of the Bangladesh Students' League. Views are personal.)